Medieval Dining Room Furniture

A Study of Period Dining Tables - Height and Width

TABLE HEIGHT

Today, we see many early tables with the stretchers very close to or actually touching the floor. However, almost all original tables were constructed with the stretchers well clear of the floor. There are several theories for this. Keeping the users feet clear of vermin and draughts, for example although, in the absence of conclusive evidence, these theories are pure speculation. From a purely symmetrical point of view, it makes some sense that whatever the extension above the stretcher top, before the turning commences, then this would be mirrored below the stretcher (see second photo below). Having said that, symmetry was never a particularly notable feature of early oak furniture!

Typically, early tables were much higher than today's preferences, 86.5cms (34") being quite normal for the majority up to circa 1600. Before the widespread use of side chairs, household occupants sat on stools and these were generally higher than chair seats. Chinnery writes in his book Oak Furniture The British Tradition that standard dining stools were made quite high (usually 23-24inches).

This boarded elm stool of circa 1550 is 54.5cms high (21.5inches) and it is highly likely that much wear has taken place on the feet bottoms, judging by the residual rot present.

© Photo reproduced by kind permission of Period Oak Antiques of Presteigne.

Joined oak stool from almost a 100 years later (Charles 1, circa 1640), is 58.5cms high (23inches). Because the turned feet are still present, we can safely say that this was pretty well the original height when made.

© Photo reproduced by kind permission of Period Oak Antiques of Presteigne.

It is reasonable to assume, therefore, that tables were made to accommodate this higher seating position or, more likely, vice versa. Many well meaning 19th/20th century owners of original tables have reduced the height, by cutting off the base of the legs. This should be considered a rather drastic course of action, although severe rot, caused through contact with damp floors, may well have forced the issue anyway. In some cases rotted/damaged table legs have been re-tipped, but not necessarily back to where they were originally. However, whatever the reason for the lack of leg extension below the stretchers, this must not be confused with how the original craftsmen intended the table to look. See also Chinnery p265: '...it is important to realise that no joined furniture was originally made in this manner'.

The table above dates back to 1560 and is just over 81cms (32inches) high, even with the stretchers almost touching the floor. Although we can only surmise, it is probable that when first made, this table would have been somewhere around 86.5cms (34inches).

© Photo reproduced by kind permission of Marhamchurch Antiques.

During the Stuart period (1603-1714), table height reduced to somewhere near where we prefer them today, 76cms (30inches). Interestingly, this coincides with the more widespread use of side chairs, as opposed to (normally higher seat) boarded and joined stools.

This table dates from 1610 and its height is 77.5cms (30.5inches). Although the feet have been re-tipped, it is likely that this later restoration represents a fair indication of what the distance between stretcher and floor, would have been originally. Note that in this example, the measurement from rail bracket to shoulder of leg turning, closely matches the distance between the lower turning shoulder to stretcher top, as well as the gap below the stretcher.

© Photo reproduced by kind permission of Marhamchurch Antiques.

TABLE WIDTH

Long tables and trestle tables, from Medieval (14th century) right up to and including the Stuart period (17th century), were usually very narrow 66cms-76cms (26ins-30ins), or thereabouts. I use the word 'usually' because, as with most things in life, there are exceptions to the rule. Two such examples are the massive tables in the Great Hall of Penshurst Place, Kent. Although wider than the norm, these tables are still relatively narrow when compared to their length. One table is 94cms (37inches) wide over a length of 665cms (21ft10ins) and the other 100cms (39inches) wide over a length of 840cms (27ft7inches). They date from the late 15th century, which is not long after the building of the manor house itself, around 150 years earlier.

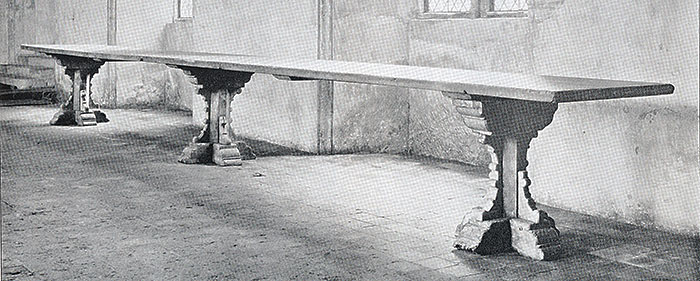

The late 15th century trestle table at Penshurst Place, from The Age of Oak by Percy Macquoid.

© Photo reproduced by kind permission of The Antique Collectors Club.

The long table above dates from 1660. It is only 75.5cms (29.75inches) wide and demonstrates that narrow tables persisted well into the 17th century.

© Photo reproduced by kind permission of Marhamchurch Antiques.

In the great halls of Medieval houses, sitters would be one side only against the wall facing inwards and be served from the other side, thus requiring less table width than would be required for sitters opposite each other. During this period large numbers of people, including servants, estate workers and craftsmen, dined together in the presence of the lord of the manor and his family. Such mass dining gave way to smaller numbers in smaller, more private, rooms, largely as a result of the Tudors dismantling the social framework around medieval barons.

Although wider tables started to become more commonplace, this characteristic narrowness of table lingered on for several centuries, long after medieval dining practises ceased.

A plausible explanation is that serving or side tables were still commonplace during the 16th and 17th century. They trace their origins back to the 'cup-board' (literally a board for cups), from the Middle Ages. The term 'court cup-board' likely originates from the French word 'court', which means short, i.e. low enough to serve from. Chinnery explains that side tables and court cup-boards, of one or more tiers, were for the purpose of 'displaying valuable plate and food, or for serving from during meals'. Wolsey & Luff commented on the Itinerary of 1617 by Fynes Moryson: '...Neither use they to set drink on the table, for which no room is left, but the cups and glasses are served in upon a side-table, drink being offered to none till they call for it'. Consequently, it would appear that the dining table only had to be as wide as was necessary to accommodate two platters or plates opposite each other. Today we tend to serve from the dining table itself and it follows that additional space is required through the centre of the table for the extra dishes, which would otherwise have been on a separate table or 'cup-board'.

This characteristic narrowness means it is possible to create a table top from one single plank. Such tables are relatively rare and highly valued in the early oak antiques market. The availability of large enough trees and the difficulties of pit-sawing large sections, would go some way to limit the potential width of a single plank table top.

The 17th century Italian table above, has been made with one single plank of walnut and is just 71cms (28inches) in width.

© Photo reproduced by kind permission of Period Oak Antiques of Presteigne.

Curiously, withdrawing tables (drawer leaf) were generally wider, 86cms-89cms (34inches-35inches), even during their Elizabethan heyday (although these were typically made up of several planks). I will cover the subject of withdrawing tables in a later blog.

The Elizabethan withdrawing table above is 89cms (35inches) in width and is typical of such pieces.

© Photo reproduced by kind permission of Marhamchurch Antiques.

You may also like to see:

What is the ideal Dining Table and Chair Height?

A Guide to Choosing the Ideal Dining Table Width

Author; By Nicholas Berry

Bespoke Reproduction Early Oak Furniture Specialist

From a small boy at infant school, I've had a passion for early furniture and architecture, embracing the 15th, 16th, 17th and 18th centuries. I've spent almost three decades designing and making replica early oak furniture (and architectural woodwork)...with my own hands!

Nowadays, together with a team of highly skilled and equally passionate craftspeople, I use that valuable experience helping clients commission, from our company, the very best in bespoke oak reproduction furniture, with a particular emphasis on personal service.

Circle Nicholas Berry on Google+ Profiles (opens in a new window)

© Early Oak Reproductions

Bibliography:

Oak Furniture - The British Tradition by Victor Chinnery

Furniture in England - The Age of the Joiner by S.W. Wolsey and R.W. Luff

Easy ways to place your order and pay...

1. You can simply place your order here on our website by using our intuitive selection boxes (on any of our product pages) and then continue through to your basket page (you'll need to register with us first - see 'Login/Register'. This will then take you through to the secure server of WorldPay, where you can pay your deposit for bespoke pieces, or full payment for accessories.

2. Alternatively, you can email or phone your order through, or visit us personally at our showroom. Click here for contact details. We accept BACS transfer, cheque, credit card or debit card payments.

However you want to order, we've made it both straightforward and safe (see our accreditation's below).

Medieval Dining Room Furniture

Source: https://www.earlyoakreproductions.co.uk/news-blog/oak-furniture-history/news-blog-5251-period-tables-height-width.php

Posting Komentar